Virtual instruction lends itself to temptation to cheat on tests. Even though many faculty are shifting to open-resource (e.g. open-note, open-internet) exams, and writing cheat-resistant assessments, and allowing flexible submission deadlines, there are still occasionally limitations that instructors want to put on how students complete tests. For example, here is my own policy, which I publish on the first page of each test:

"You may use all existing resources at your disposal (e.g. notes, course videos, resources found on the internet) to respond to these questions. However, you are not allowed to communicate with anybody else about this assignment (including, but not limited to: other students currently in this class, prior students, family, friends, or strangers who might respond to online discussion board/forum inquiries). By submitting your responses to this assessment, you certify that you agree with the statement: 'I have done my own work and have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work.'"

I also require students to cite all allowed sources (e.g. websites, textbooks, etc.) that they referred to when completing each question.

The conversation of whether "cheating" (a.k.a. "collaboration" outside the context of a classroom) should be discouraged is a valid one, which will continue elsewhere. For now, let us assume that we want to use a traditional assessment (written test/exam) to measure how well an individual student is able to complete important tasks by applying and demonstrating their understanding of subject matter. And, let us assume that it is important to identify and report academic dishonesty, and that we choose not to turn a blind eye to the situation when we suspect that a student has cheated. After all, many of us have institutional policies that require instructors to report suspected cheating, like Fresno State Academic Policy 235, which reads, in part (emphasis mine):

"When a faculty member responsible for a course has reason to believe that an action of a student falls within one or both of the above definitions, the faculty member is obliged to initiate a faculty-student conference."

It is worth reiterating that my interest in writing this blog series on Academic Dishonesty is based on my experience during the spring 2021 semester, when I encountered quite a bit of cheating in a virtual class. Once I became aware of the issue, I then spent way too much time (probably because I'm a scientist?) analyzing student exam submissions to see if I could improve my ability to detect academic dishonesty. Based on individual conversations I had with students that I accused of cheating, I found that there are a couple of easy and robust methods for spotting cheating. While I would be surprised if both of these approaches are new to you, perhaps one will be new and useful. These methods can be effective at identifying two predominant forms of cheating: students sharing answers with each other, and a student plagiarizing content from an external source.

Two Methods for Detecting Cheating

1. Perform a Web Search

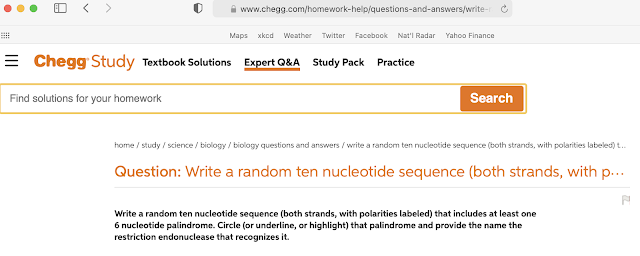

As I mentioned in the previous post, performing a web search with a clause or phrase from your exam question/prompt is a great way to discover whether any of your students have posted the content on the internet. This only works if the content is hosted on web pages that are indexed by search engines. I was (pleasantly?) surprised to find that Chegg web pages are indexed, and a future post will explore how to interact with Chegg to perform additional investigation of academic dishonesty, including obtaining the identities of those involved. If you haven't heard of Chegg before, it is, in part, a "tutoring service" to which students pay for an account, after which they can pose questions to "Experts" who will provide answers. Here's one example of one of my exam questions that was posted on Chegg:

2. Look for Shared Mistakes

For the situation where students are relying on external sources (not other students) to cheat, one way to spot plagiarism is to look for vocabulary that you did not use in class.

For example, in my genetics class, one question asked students to "Describe the type of experiment that a geneticist would need to perform…" Many students mentioned techniques we never discussed at all in this class, like RT-PCR and northern blotting, and that information came from uncited internet sources, thus plagiarism, and thus cheating.

Another question on the same exam prompted several students (who had cheated, all using information from the same uncited source) to use the phrase "structural genes," which is a phrase I had never used during class.

Here's a different take on the same approach: I also scrutinize student responses for shared misspellings. This is a great way to detect even subtle cheating. Students make this mistake frequently. Here's a relevant example of an exam question that was posted to Chegg:

Well before I discovered that this question had been answered by a Chegg Expert, I had already suspected two students of cheating. The students had happened to create the same six-letter palindrome (which in itself is extremely unlikely). Based on the palindrome they used, the correct answer to "name the restriction endonuclease that recognizes it" was "SmaI" - but both students had transposed the first two letters of the name of the restriction endonuclease, so their answers were both "MsaI."In practice, I would describe the gestalt of this approach as:

If you look at a student response and you wonder to yourself, 'How the heck did they come up with that answer?,' then note it. If you later find that another student did the same weird thing, then academic dishonesty has likely taken place.

Because I require students to cite all of the sources they use while completing the exam, it is easy to identify where unexpected responses came from. In such a case, then I wouldn't penalize the students for collaborating on an answer, because they had just independently identified the same source. However, in many cases I found that some students did cite the source, but others did not. Then, the students who did not cite the source would not earn full points and/or be disciplined for plagiarism.

In the next and final post, "Dealing with it," in the Academic Dishonesty series, I'll describe my interactions with Chegg, with institutional policies, and with the students as we resolved the academic dishonesty charges.

No comments:

Post a Comment