|

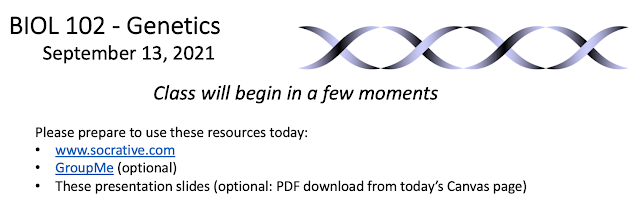

| Example before-class slide |

Authored by a university professor of genetics. More importantly, I love to learn, to innovate, and to proffer effective best practices in all things pedagogy. My values: discipline-agnostic professional development in education, creating accessible learning materials, improving course material affordability, and above all else improving student interaction and inquiry in the classroom.

Saturday, September 18, 2021

HyFlex: Pre-Class Experience, pt 1

Monday, September 6, 2021

Build Your Own HyFlex: Tech Setup

About technology

- I never have dry erasers and I have a greater choice of colors to choose from

- erasing the board is a lot faster when it is digital, and most importantly to me

- I can load images, lecture slides, etc. into the digital whiteboard and manipulate and annotate them

Course Design and Needs

HyFlex Setup

To achieve these goals, I launched Zoom on my laptop, which I connected to the room projector. The built-in laptop camera was pointed at the projection screen. Thus, during the parts of class when I had laptop content to share (like movies), I could use the Share Screen feature in Zoom to let the Zoomers see the video and hear the audio, while the Roomers saw all of this projected to them in the context of my laptop screen.Improvements

Now I’ve had time to bring extra tech gear from home, which I didn’t have on hand at school the day I had to throw this together. Here’s how I've revised my approach to improve tablet-based presentations. |

| A tablet (foreground) used as a "Share Screen" source in Zoom is clearly displayed to Zoom participants (background) |

HyFlex: Take One

Resulting from COVID-19, many classes at California State University, Fresno ("Fresno State") were moved to a virtual format in March, 2020. Over the 2020-1 academic year, a handful of classes returned to in-person instruction. In anticipation of the need for continued flexibility in course modality, Fresno State renovated several classrooms to accommodate HyFlex. During summer 2021, some of my colleagues and I engaged in a professional development activity to prepare for teaching HyFlex classes, where some students are present in the classroom ("Roomers") while others attend synchronously and remotely, in our case using Zoom ("Zoomers").

This series of posts will explore both the technological and pedagogical aspects of implementing and managing a HyFlex course

Contents

8/21/21 Fall '21 Pre-Instruction Fresno State HyFlex Notes

Saturday, August 21, 2021

Fall '21 Pre-Instruction Fresno State HyFlex Notes

Colleagues - I'm writing on Saturday morning, August 21, 2021 - instruction starts in two days! I just went to campus to test some teaching workflows in the HyFlex room I'm assigned (Conley Art 101). Its setup is different than the Social Science building rooms we practiced in previously, but I hope these few tips and thoughts about HyFlex instruction will be helpful to know in advance.

Caveat: what I describe here might not be exactly the same in your HyFlex classroom, so please test out workflows before you teach, if possible.

Also, please note that it appears that Tech Services has left a shortcut on the instructor PC station desktop to the (generic) instructions for using the HyFlex setup. I call them generic because some of the content doesn't apply to the way CA101 is set up, but I imagine they're accurate for most of the HyFlex spaces. CFE has also compiled a list of documents with tips and strategies about HyFlex.

Introduction and Goals

The HyFlex genetics class I'm teaching uses blended learning ("flipped classroom.") Students are assigned homework exercises and video lectures to access prior to class, and much of my in-class time is spent working through the solutions to exercises, answering student questions, and engaging in discussion. In the past, instead of using the classroom white board, I've connected my tablet to the classroom projector (there are various ways to do this, which aren't important here). This lets me project the tablet contents to the class, and I can annotate on the tablet screen - so it is just a projected digital whiteboard. Also, part of helping students with digital literacy in genetics occasionally requires me to demonstrate the use of an online database or web-based analysis tool, so I also like to be able to display a web browser.

Thus, the main technological approaches I use don't really require me to show videos to roomers and Zoomers. I mainly need to project:

- my tablet

- a web browser window

- a live camera shot of me (for normalcy/engagement during Q&A and discussion - basically anytime I'm not showing work on the tablet)

I also need a way to collect synchronous feedback from roomers and Zoomers.

Here's what I learned while I tested these four approaches in CA101, followed by two (example) things I still don't know how to do!

Sharing Video

Just in case, I did try sharing video content and to check the settings required for the Zoomers to hear the audio. Because I'm an Apple user, and because I like to set up for class in advance (e.g. open all necessary windows, videos, websites, etc. I want to use during class and share to the Zoomers), I don't want to have to try to set up the instructor station PC in the ten minutes between when I get into the classroom and when class is supposed to begin. My strategy is to set up my Apple laptop with all of the content I want to share. Thus, I needed to learn how to connect the laptop so that I can share its screen.

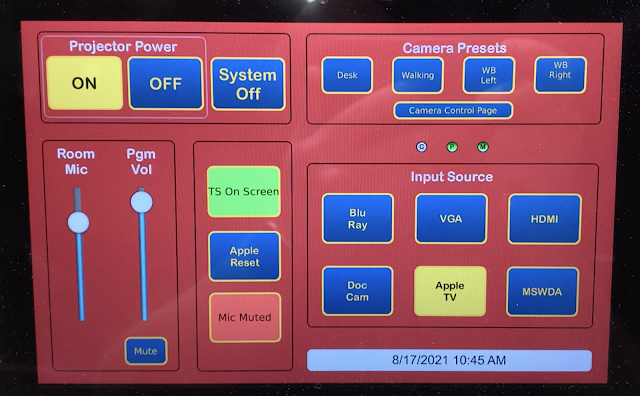

This means I either physically connect the laptop to the VGA or the HDMI port that is associated with the Extron controller (I used HDMI). Then, I make sure that the Extron "TS on Screen" button is displayed, as below, and not "Zoom on Screen."

Caveat: I don't think that "TS on Screen" is the Extron button language that is present in other classrooms, but all of the classrooms have a "Zoom on Screen" button that toggles between it and the second option, so whatever classroom you're in, you want to see whichever version of that button that does not read "Zoom on Screen."

|

| The controller screen was changed between when this photo was taken (8/17) and today (8/21), but it is still a good representation of the layout (the "Room Mic" slider no longer exists) |

In this configuration, with "HDMI" selected on the Extron controller as the Input Source (not "AppleTV" as shown above), my laptop screen is mirrored to the room projector and is also displayed to the Zoom participants. The same works for connecting to the VGA port.

So, this is the workflow for sharing external device content (i.e. anything other than the instructor station PC), in CA101 at least. This is great for sharing web browser windows, documents or anything else. It is worth noting that the entire device screen is shared, not just a specific window, because we're not using Zoom to "Share Screen" so we don't get the same control over what is shared.

However, the audio works differently. In the room, there is an in-room microphone (I assume one associated with the in-room camera) that picks up room audio and feeds it to the Zoomers. However, the Extron video sources don't feed audio directly to the Zoomers, because those sources are connected directly to the Extron controller and are not screen-shared through Zoom. The point here is that any video content you do not share directly through the "Share Screen" button in Zoom is not able to have its audio also directed, through Zoom, to the Zoomers. Instead, what happens is that the in-room speakers play the audio to the roomers, and the in-room microphone also picks up that audio and plays it to the Zoomers. In CA101, the quality of the audio delivered to the Zoomers this way is not poor quality, but the main problem you might encounter is that, while the room microphone is on, all of the Zoomers will also hear any room noise that is occurring. This is what you want from a room mic, of course, but perhaps not while you're trying to play a video. By the way, the "Pgm Vol" slider on the Extron controller is what controls the audio output volume of a device you've connected. So, if you are playing a video from a connected laptop and it isn't loud enough, increase the volume using the Extron touchscreen.

So, it seems you have two options for sharing video with audio. Either load the content on the instructor station PC, and share that content using the "Share Screen" feature in the Zoom meeting, in which case you should follow the HyFlex instructions for how to set the Zoom audio sharing settings so the computer audio is indeed played to the Zoomers. If, like me, you don't want (or have time) to set up videos on the instructor PC before class starts, then connect your device as described above. I would encourage you to check with your Zoomers, though, to ensure they're getting good enough quality audio!

It is also worth being aware that the "Mute" button in Zoom does exactly what you would hope and expect: it turns off the room microphone. So, if you choose the "direct connection" option above to play a video, your Zoomers are relying on the room mic to convey the audio to them, so don't mute while you're playing a video! In theory (I didn't test this), if you're using the other approach and playing a Zoom "Share Screen" video, then you would want to engage your Mute button in Zoom so the Zoomers aren't hearing the room audio in addition to the audio from the source.

Tablet Projection (using AppleTV)

Use the "Screen Mirroring" option to connect your Apple laptop or iPad or iPhone to (in my case) the CA101 AppleTV. Make sure the Extron is set to "TS on Screen" and the Input Source as "AppleTV." Now, the device is projected to the room and is also shown to the Zoomers. As above, the video of you (as the instructor) that your Zoomers always see is whatever is currently being shared: the Extron input source. So, they don't see you at all - not even as a picture-in-picture thumbnail. The way to let the Zoomers see you is explained below. In all of the sharing options I've described so far, the Zoom audience does not see you at all - just the screen of the device you are sharing.

Live Camera (and room audio quality)

As described in the Tech Services HyFlex instructions, in Zoom, "Share Screen" and then select the "Advanced" tab and select "Content From Second Camera." This will engage the room camera to display whatever it is configured to display. In CA101, two "Camera Presets" (see Extron controller image above) that are functional: "Desk" zooms in to show the instructor station, and "Walking" displays the entire front of the room as show below.

|

| The "Walking" camera preset in CA101 as viewed from the instructor station monitor |

Note a few things about this particular camera view, that you might want to consider in your room.

First, part of the ceiling blocks the view of the projection. Also, the camera is not in the middle of the room. So, in this setup, I would not opt to use the "second camera" Zoom view as the default video to send to Zoomers, because it doesn't display all of the projected content, and the projected content is distorted and isn't as legible and detailed as when I use the first technique above and share my device screen directly using the Extron controller.

Second, the first two rows of students are visible. It is probably a good idea to let those students know that their heads and whatever might be on their computer screens could be displayed to the Zoomers and also recorded on the Zoom video, if you're recording your classes. This is, essentially, no different than having somebody sit behind you in class and look over your shoulder to see what might be on your device screen. However, if you're recording, there might be additional considerations.

Third, while you're sharing the room video to the Zoomers, the roomers are not seeing the room video projected to them - they still see whatever source is selected on the Extron. That is why, in the photo above, the top right thumbnail of a Zoom user (me - the instructor station) is shown as a black screen with white handwriting - that's my iPad connected to the AppleTV, which is still selected as the input source on the Extron. In other words, the only time the same video content is fed to the roomers (classroom projector) and Zoomers (their Zoom windows) is when a device is directly connected to the room and the Extron controller is being used to select which input source to project.

In this view, and while using the direct-connection screen sharing, I checked the quality of my audio as I talked out loud while walking around the classroom. In CA101, the microphone is pretty good at picking up audio from all corners of the room. However, the sound definitely has lower quality in the rear of the room (and especially when wearing a mask!) So, this only serves to reinforce two important things: 1) use your "teacher voice" and speak slowly and enunciate, or the Zoomers won't understand you, and 2) be particularly careful about this if you, like me, enjoy walking around the room while teaching. If you stay at the front of the class, then this probably won't be as much of an issue. Nevertheless, remember to inquire to your Zoomers about the quality of your audio!

Collecting Student Feedback Live

With less than two days until my first HyFlex class, I'm still puzzling over this one. How can we facilitate roomers and Zoomers interacting synchronously during class with me (e.g. a single mechanism for back-channel communication) or with each other? I'm envisioning two scenarios. In the first, I have a technical issue while starting class, or the start of class is delayed, and I need to communicate quickly to the Zoomers in real time to let them know what's going on. For the second, I'm thinking about, as a random example, what if I wanted to poll students or collect other formative feedback.

Here's the background context: I don't think I want the Roomers also to be logged into Zoom just to participate in Zoom polls and/or to use the Zoom chat. That's potentially tough on the wifi system, and also an issue when somebody forgets to mute their microphone or not mute their device speakers (feedback!) I'd like to use a common app or platform to allow the roomers and Zoomers to (as an example) type questions or feedback. The main drawback, as I see it, of not using Zoom for this is that it requires the Zoomers to switch back and forth between Zoom and whatever other app. It also means the roomers would need a device if they wanted to participate.

My current inclination (which might change before Monday!) is to have a class Discussion Board open on our LMS website, for students and me to use before and during class: for example, if I'm having to start class a few minutes late because the teacher prior to me didn't clear the classroom on time, and I don't want my Zoomers to see "Waiting for host to start the meeting…" at five minutes past the start of class and then give up and log off, then if I've told everybody in advance that I'll use the Discussion Board for real-time communication about class meetings, the Zoomers can check there for updates. The drawback to the Discussion Board is that it isn't anonymous, which I think is a huge negative.

Ideally, I think I'm looking for an app or platform that allows threaded text discussions (keeping all comments time-stamped and/or in chronological order) from anonymous participants. How would you handle this? Slack or

Still Totally A Mystery…

The only thing (at present!) I haven't figured out is how to control the volume of audio being played in the room by Zoom. For example, how loud people on Zoom will sound on the classroom when they unmute and talk. In CA101, that in-room speaker volume is really quite loud!

Good luck skill on the first day of class, my friends - we've got this! Just remember: be honest with the students and set expectations for them at the start of class. Everything will work out. Model a growth mindset!

Keep an eye on this space - I'll be adding additional posts about other first day of class thoughts, and an outline of best practices for managing a HyFlex meeting. - Joe

Monday, June 21, 2021

Summer Reflections: Academic Dishonesty: investigating and disciplining

Once an instructor has identified alleged academic misconduct (cheating), then you have more choices to make about whether and how to proceed. In my experience, by this point I've already invested an unfortunate amount of time just detecting cheating. I'm not feeling interested in pursuing the formal steps necessary, because it won't benefit me.

However, at least from a legal/procedural perspective, after lots of consultation with peers, staff, and administrators, I decided that I should follow my institution's policy on cheating. One main reason for this is to ensure that students are provided with due process. If an instructor takes any disciplinary action (like assigning zero points on a test, or assigning a failing grade) based on suspicion of cheating, then the student can later contest that action in a formal appeal. Practically speaking, this just triggers even more time-sucking meetings and procedures.

So, here, I will

- describe the formal process I followed

- reflect on how my meetings with the students went, and

- explain how I documented evidence of students cheating using Chegg

Formal Academic Dishonesty Investigation Process

Briefly, my university requires that any suspicion of cheating must be explored by the faculty member either A) holding a Faculty-Student Conference, or 2) referring the matter to the Department for a Departmental Hearing. The agenda of the Faculty-Student Conference, which need only be attended by the faculty member and the student, is for the faculty member to present the student with the charge and evidence of cheating. If the student admits to cheating at this time, then the instructor can impose an academic sanction within their power as an instructor (i.e within the scope of the class, like assigning zero points or a failing grade), and the instructor can also recommend additional sanctions for the Dean of Students to consider, like not allowing the class to be repeated for credit (in the case of the student failing the class) or expulsion from the University. If the student does not admit to cheating or does not agree with the assigned sanction, then the instructor advances the investigation by notifying the Department Chair, and the process repeats with a Departmental Hearing.

Regardless of the outcome of the Faculty-Student Conference, the instructor must file an "Instructor's Report of Cheating or Plagiarism" with the Dean of Students. Here, the instructor not only provides a narrative of the situation, but also must collect and submit a number of pieces of information that can take some time to assemble, like the date of the incident, the unique course section number, the name and ID number of each student, the documentation of cheating (e.g. the student's work as well as evidence of cheating), and copies of all communication the instructor has had with the student about the alleged cheating. I make this point now just to alert you of the value of knowing in advance what will be needed, so that if you find yourself in the same situation, you'll know what records to keep and organize in advance.

Because I identified several cases of cheating last semester, after holding multiple individual Faculty-Student Conferences, I then spent additional hours submitting the individual Instructor's Reports documenting the outcomes of those Conferences.

About the Faculty-Student Conferences

I prefer to avoid confrontation at all costs, so I was not eager to have these one-on-one meetings. I was also skeptical whether students would respond to emails in which I informed them that we needed to set up individual Zoom meetings to discuss whether they cheated. At the very least, I was glad that my first exposure to this process was during a global pandemic, because having these conferences over Zoom made me feel a bit more at ease than I would have been for in-person meetings.

It is important to note that, before I sent individual emails requesting Conferences, I had announced to the entire class that I had found evidence of extensive cheating using the Chegg website and that I would be contacting individual students in the near future. Thus, many of the students knew that they had been caught, so they were probably anticipating that email from me. In fact, my announcement that I had received data from Chegg about who had been posting and viewing answers to exam questions (details below on how to do that) prompted an insightful chain of texts on GroupMe (an external chat platform that students often use to message each other outside of the class LMS platform):

|

All of the students I emailed responded promptly, and none of them in an aggressive or overly defensive manner. They were all polite and respectful.

When it was time to meet, this is the approach I took: I started the conversation by explaining the purpose of the meeting and the process (including a description of how I was following the University policy, what the potential outcomes were, and the student's rights), and asked if the student had any questions up front. Then, I explained the evidence and why I thought it constituted academic dishonesty, based on the academic policy definition. I next asked the student if they agreed with my perspective (i.e. that cheating had occurred). If they did agree, then I explained the sanction I was going to make (usually zero points on the cheated question or the entire exam, depending on the severity). I ended by asking the students to please not do this again, emphasizing the worse things that could happen, and reinforcing the point that they're paying me to be their teacher, and that I hoped in future they'd come to me with questions.

In the conferences themselves, I found that most of the students knew they had been caught; some even seemed relieved to be able to talk about it and explain themselves - it had clearly been weighing on their conscience. Most students were, I think, appropriately apologetic.

However, there was one group of three students that didn't use Chegg to cheat, and I wasn't able to find any other evidence on the internet of the source of their exam answer - so I suspect that the three of them collaborated to produce that answer. When I individually confronted these three, none of them confessed, although they also didn't provide any believable justification for how they might have submitted the exact same (and very wrong) answer as two other students. I asked each student what process they had used to come up with the answer; could they explain their reasoning to me? None had any remotely relevant answer. One said they were drunk when completing the exam, so they didn't remember how they completed it (but they did assure me that later, when sober, they asked the friends they had been with if they had been cheating, and the friends said that they hadn't noticed anything odd).

Documenting evidence of cheating: Chegg

In addition to guidance I provided in previous posts about designing cheat-resistant exams and about detecting cheating, here's what you need to know about working with Chegg.

Chegg is a commercial website that does lots of things related to providing students with study resources, textbooks, and other things. The aspect of Chegg that seems to me to be most controversial is that students can pay for a "Chegg Study" account and then ask questions of "Chegg Experts." From their website:

"Ask an expert anytime. Take a photo of your question and get an answer in as little as 30 mins. With over 21 million homework solutions, you can also search our library to find similar homework problems & solutions. Our experts' time to answer varies by subject & question (we average 46 minutes)."

So, what most faculty dislike about Chegg is that students can pay for an account (of course despite the fact that they're already paying tuition for us, the experts, to help them learn - there's no reason they should pay Chegg, too!), upload any sort of course material (like homework questions, exam questions) and get a pretty rapid answer. Also, anybody else who has a paid Chegg account can also view every other member's questions and the provided answers.

My totally uneducated guess is that Chegg's "Experts" aren't really such experts. I don't know how the "Experts" are hired and vetted, but I do know from my experience with students cheating using Chegg is that the answers are not always correct!

Not surprisingly, Chegg asserts that their business, "should never be used by you for any sort of cheating or fraud" (see their Honor Code webpage). It is clear, though, that lots of students use Chegg to cheat, in part because Chegg has a dedicated system for faculty to request an Honor Code Investigation. So, here's another opportunity for faculty to spend lots of time investigating potential academic dishonesty.

In my previous post, on identifying cheating, I mentioned that an easy well to tell if your exam questions have been posted to Chegg is to perform a web search with text from the question. That's how I discovered that my materials had been submitted to Chegg. Here's one really irksome thing about Chegg: they don't provide faculty with accounts to let us investigate academic dishonesty. Without paying for a Chegg account, you can see questions that have been submitted, but not the answers. Of course, what I need, beyond seeing that my exam question is on Chegg, is to see the expert response, so I can tell if it matches the submitted answers of any of my students. I did register for a free account on Chegg, but that doesn't let you see the Chegg Expert answers. One solution, of course, is to pay Chegg for the privilege of seeing the answers, but I didn't really feel like I should help financially support this company, so I didn't - although I did suggest to my university's Student Conduct Office that they might consider paying a staff member for a single license so that they could conduct better investigations on behalf of faculty. There is a way, eventually, to get the answers (detailed below).

Here's a great example of hypocrisy: because I signed up for a free Chegg account, I now receive the occasional solicitation email from them. Last week, the subject line read, "Do you know the best way to solve that Biology problem?" The body contained, in part: "Give your GPA a boost. Chegg Study to gain access to millions of problems posted by students like you, fully solved by Chegg subject experts." But yet users are cautioned not to use Chegg to cheat…

Chegg Honor Code Investigations

The good news is that Chegg does a pretty awesome job at responding to faculty inquiries about cheating. They state that, "We respond to all Honor Code violation escalations from faculty within 2 business days and we will share usage information - including name, email, date, IP, and time stamps."

Here's what a faculty member needs to request Chegg to investigate potential cheating:

- The URL of each Chegg webpage that you claim has your course content. This can be problematic, because multiple students can post the same question, and they'll appear on separate Chegg pages with separate Expert responses - so it is likely you might not find all of your content.

- Your contact information

- The exam start day and time and end day and time (maximum of 24 hours apart). As far as I can tell from my experience, Chegg simply uses this information to know what date/time range in which to search their server logs for account activity. Because I was running asynchronous exams, though, sometimes my exams were open for multiple days before they were due, which isn't optimal for this sort of limitation.

- The name of your Dean or administrator for academic affairs. In my case, I provided the name of my Dean of Students.

- A signed copy of an investigation request on university letterhead.

It only took a day or two for Chegg to send me the results of their investigation, in the form of a spreadsheet file with the following information.

One tab contains "Asker Detail" - these are the Chegg users that submitted the questions on the URLs I reported:

- The timestamp of when the question was submitted, and when the Chegg Expert answer was posted

- The Asker email address

- The Asker name

- The Asker IP address

- The Asker School Name

- The Question

- The Answer

The second tab contains "Viewer Details" - these are the Chegg users that viewed the Expert answer pages. The content of that tab is almost identical to the first tab.

This is useful information for a faculty to have! Names and email addresses of people who submitted questions, and all of the people who viewed the answers! But with the following important caveats…

- When students register for a Chegg account, they don't necessarily use their university email address

- When students register for a Chegg account, they don't always use their real name

- Because the answer is originally provided on Chegg as a webpage, the "answer" is formatted as HTML, and that is how the answer is provided in this spreadsheet report: as HTML in a single cell in the spreadsheet. If the Expert's answer involves images, you'll have to grab those image URLs out of the answer text and load them separately on your web browser, or save the entire HTML content as a text file and load that in your web browser. In particular, I'm quite unsure how long those images, which are hosted by Chegg, will remain active, especially because once you notify Chegg that your content is on their site, they remove it! That's a good thing, unless you want that content to remain so that you can continue using it as evidence of an ongoing academic dishonesty investigation on your campus! So, here's another critical point: save all Chegg evidence (URLs, perhaps screen shots or PDFs of all Chegg webpages) before you ask them to launch an Honor Code Investigation.

- Students might be sharing Chegg accounts, in which case you'll only identify the account holder!

By the way, I pressed Chegg (faculty can email their faculty team at faculty@chegg.com) about students registering for accounts without using their real name. After all, I pointed out, students have to pay for Chegg accounts to post questions and view answers, and so they must have had to use their legal name associated with their form of payment. So, would Chegg provide that name to me? No. Their response (emphasis mine):

"Unfortunately, because we are bound by privacy laws and our privacy policy, we may not investigate specific accounts, names, users, or email addresses. We are only able to share information related to the specific URLs reported when an Honor Code investigation is opened. However, if a student requires additional account information as part of an ongoing academic integrity investigation, we are able to release account activity directly to the owner of the account. These requests can be submitted as a ‘My Data request,’ or the student is welcome to reach out to support@chegg.com directly with any questions regarding their account. Also, to help clarify, it is not possible for us to determine whether any particular account has had unauthorized access to a reasonable level of certainty. The information visible to us and made available in investigation results is simply activity on the account, with no indicator of whether the activity is generated by the individual, someone they may have given their account credentials to, or some unauthorized actor. We can only release personally-identifiable information (PII), including billing or payment information, in response to an issued subpoena. This is due to stringent privacy laws which prohibit our release of student PII except in specified cases. Once we have a subpoena, we can promptly provide this information. Feel free to reach out with any additional questions."

Like a University would request a subpoena to get student information to assist in an academic dishonesty investigation!

It is also worth noting, from this quote, a good point related to account-sharing: there is no way for Chegg to know what person is accessing materials on their website - only what account is logged in. So, be cautious when accusing students of cheating - presume innocence at first!

Intellectual Property Rights

As I mentioned above, Chegg will take down URLs on their site in response to an Honor Code Investigation. This is part of their statement that

"Chegg respects the intellectual property rights of others and we expect users of our websites and services to do the same. Chegg is designed to support learning, not replace it. Misuse of our platform by any user may have serious consequences, up to and including being banned from our sites or having an academic integrity investigation opened by the user’s institution.

In keeping with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, we will respond promptly to valid written notification of claimed infringement regarding content posted on Chegg sites. Please note that Chegg may forward the written notification, including the complainant’s contact information, to the user who posted the content. It is also our policy to disable and/or terminate the accounts of users who repeatedly infringe the copyrights of others.

We respond to DMCA content takedown requests within 2 business days and will remove material in accordance with the DMCA."

Conclusion

For a company with Chegg's business model, it is nice to see that they do comply quickly with Honor Code Investigations and with DMCA requests. However, we're fighting in an arms race.

I do not care to tally how many hours I spent this semester 1) looking for hints of cheating on exam material, 2) investigating cheated material present on the internet, 3) communicating with campus administrators and with Chegg, 4) assembling the Honor Code Investigation document, 5) analyzing the Honor Code Report, 6) contacting students and holding multiple Faculty-Student Conferences, and 7) submitting a campus Instructor Report of Cheating or Plagiarism for each of those students.

This is the conclusion of the Summer Reflections: Academic Dishonesty series of posts. I've now detailed lots of advice and procedures for helping students learn what not to do, what the potential punishments of cheating can be, ways to proactively dissuade students from cheating, writing cheat-resistant (and cheat-detecting) exam questions, how to spot cheating, and now how to deal with it when it happens. Even though it is an uphill battle with one instructor and numerous students who have much more incentive and collective time to cheat, I still think it is a battle worth fighting.

Monday, June 14, 2021

Summer Reflections: Academic Dishonesty: detecting cheating

Virtual instruction lends itself to temptation to cheat on tests. Even though many faculty are shifting to open-resource (e.g. open-note, open-internet) exams, and writing cheat-resistant assessments, and allowing flexible submission deadlines, there are still occasionally limitations that instructors want to put on how students complete tests. For example, here is my own policy, which I publish on the first page of each test:

"You may use all existing resources at your disposal (e.g. notes, course videos, resources found on the internet) to respond to these questions. However, you are not allowed to communicate with anybody else about this assignment (including, but not limited to: other students currently in this class, prior students, family, friends, or strangers who might respond to online discussion board/forum inquiries). By submitting your responses to this assessment, you certify that you agree with the statement: 'I have done my own work and have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work.'"

I also require students to cite all allowed sources (e.g. websites, textbooks, etc.) that they referred to when completing each question.

The conversation of whether "cheating" (a.k.a. "collaboration" outside the context of a classroom) should be discouraged is a valid one, which will continue elsewhere. For now, let us assume that we want to use a traditional assessment (written test/exam) to measure how well an individual student is able to complete important tasks by applying and demonstrating their understanding of subject matter. And, let us assume that it is important to identify and report academic dishonesty, and that we choose not to turn a blind eye to the situation when we suspect that a student has cheated. After all, many of us have institutional policies that require instructors to report suspected cheating, like Fresno State Academic Policy 235, which reads, in part (emphasis mine):

"When a faculty member responsible for a course has reason to believe that an action of a student falls within one or both of the above definitions, the faculty member is obliged to initiate a faculty-student conference."

It is worth reiterating that my interest in writing this blog series on Academic Dishonesty is based on my experience during the spring 2021 semester, when I encountered quite a bit of cheating in a virtual class. Once I became aware of the issue, I then spent way too much time (probably because I'm a scientist?) analyzing student exam submissions to see if I could improve my ability to detect academic dishonesty. Based on individual conversations I had with students that I accused of cheating, I found that there are a couple of easy and robust methods for spotting cheating. While I would be surprised if both of these approaches are new to you, perhaps one will be new and useful. These methods can be effective at identifying two predominant forms of cheating: students sharing answers with each other, and a student plagiarizing content from an external source.

Two Methods for Detecting Cheating

1. Perform a Web Search

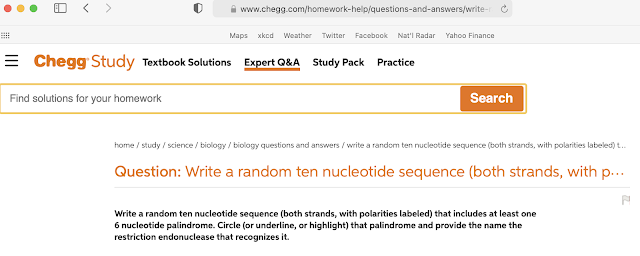

As I mentioned in the previous post, performing a web search with a clause or phrase from your exam question/prompt is a great way to discover whether any of your students have posted the content on the internet. This only works if the content is hosted on web pages that are indexed by search engines. I was (pleasantly?) surprised to find that Chegg web pages are indexed, and a future post will explore how to interact with Chegg to perform additional investigation of academic dishonesty, including obtaining the identities of those involved. If you haven't heard of Chegg before, it is, in part, a "tutoring service" to which students pay for an account, after which they can pose questions to "Experts" who will provide answers. Here's one example of one of my exam questions that was posted on Chegg:

2. Look for Shared Mistakes

For the situation where students are relying on external sources (not other students) to cheat, one way to spot plagiarism is to look for vocabulary that you did not use in class.

For example, in my genetics class, one question asked students to "Describe the type of experiment that a geneticist would need to perform…" Many students mentioned techniques we never discussed at all in this class, like RT-PCR and northern blotting, and that information came from uncited internet sources, thus plagiarism, and thus cheating.

Another question on the same exam prompted several students (who had cheated, all using information from the same uncited source) to use the phrase "structural genes," which is a phrase I had never used during class.

Here's a different take on the same approach: I also scrutinize student responses for shared misspellings. This is a great way to detect even subtle cheating. Students make this mistake frequently. Here's a relevant example of an exam question that was posted to Chegg:

Well before I discovered that this question had been answered by a Chegg Expert, I had already suspected two students of cheating. The students had happened to create the same six-letter palindrome (which in itself is extremely unlikely). Based on the palindrome they used, the correct answer to "name the restriction endonuclease that recognizes it" was "SmaI" - but both students had transposed the first two letters of the name of the restriction endonuclease, so their answers were both "MsaI."In practice, I would describe the gestalt of this approach as:

If you look at a student response and you wonder to yourself, 'How the heck did they come up with that answer?,' then note it. If you later find that another student did the same weird thing, then academic dishonesty has likely taken place.

Because I require students to cite all of the sources they use while completing the exam, it is easy to identify where unexpected responses came from. In such a case, then I wouldn't penalize the students for collaborating on an answer, because they had just independently identified the same source. However, in many cases I found that some students did cite the source, but others did not. Then, the students who did not cite the source would not earn full points and/or be disciplined for plagiarism.

In the next and final post, "Dealing with it," in the Academic Dishonesty series, I'll describe my interactions with Chegg, with institutional policies, and with the students as we resolved the academic dishonesty charges.

Monday, June 7, 2021

Summer Reflections: Academic Dishonesty: cheat-resistant questions

This past semester (Spring 2021), I taught entirely online classes because of COVID-19 restrictions. In general, I really enjoyed and grew professionally from this experience. One drawback of any virtual course, though, is deciding whether and how to assess students using tests/exams. I chose to use online, untimed, un-proctored exams, so I knew that I should devise cheat-resistant exam questions that simultaneously help me easily detect cheating. This post describes my course design and exam design, including the types of questions I created that were successful at helping me spot cheating.

Course Design

My philosophy was heavily influenced by my professional development training in online course design as well as messaging from my campus and from my students. The argument, especially during a pandemic, was for providing flexibility. I experienced a lot of pushback on the idea of using remote proctoring services due to concerns about privacy and equity. Also, in part because of the potentially low-income and rural student population here, there were acute concerns about availability and stability of internet access and whether some students have safe and quiet places in which to complete timed exams.

I decided to assess my undergraduate course in genetics, with about 70 upper-division biology majors, with four midterm exams and a final exam. I also provided lots of lower-stakes assignments and exercises, so that the final grade would comprise:

30% Attendance and Participation (including asynchronous options for participation)

20% Exercises (homework, problem sets, etc.)

30% Midterm exams (the top three exam scores are used; the lowest score is dropped)20% Final exam

Exam Design

Thus, exams made up half of the student grade. It is worth noting here that my grading scale is atypical:

100-80% = A

80-60% = B

60-40% = C

40-20% = D

0-20% = F

I've written on the rationale for using this scale before. Briefly, I align all of the questions on my exams (and the points available for each) with Bloom's taxonomy, so that roughly 20% of points available on exams are lower-level Bloom's type work (like multiple-choice), and then 20% a bit more cognitively difficult, and so on. Thus, only students who are able to demonstrate competence at all levels (including the highest level, "Create") will be able to earn an A.

The reason I spend so much effort crafting these exams, and using this Bloom's Grading structure, is that this approach helps produce cheat-resistant exams. Students may easily be able to cheat on the lower Bloom's activities, like fill in the blank, true/false, and matching; with my grading scale, that might only earn them, at best, a C grade. Further, that's the scenario if I don't catch them cheating; if I do, then the grade is even lower. When students attempt the higher-level Bloom's questions that require them, for example, to analyze a dataset and then justify their answer, they necessarily produce unique responses. This makes it easy for the instructor to spot plagiarism.

Ultimately, designing exam questions to prevent cheating (or at least to make it easy to spot cheating!) does take effort. There is no perfect solution to writing cheat-proof exams, but you can improve their cheat-resistance.

There is a clear and direct trade-off between how cheatable an exam is and how much effort the instructor puts into creating the questions and into grading the responses.

Attempting to be an understanding and supportive instructor, this past semester I made all of the midterms and the final open-internet and asynchronous. Frankly, for an online course, and because I didn't want to use online proctoring systems, there's no practical way to prevent students from using all of the resources available to them. Plus, I've always allowed open-note exams, and I found no reason to change that policy. In terms of the amount of time given, I typically published the exams three days before they were due.

With this framework, students clearly have lots of opportunity to cheat by collaborating with each other, which was the one thing I specifically prohibit, including in this policy on the front page of each exam:

You may use all existing resources at your disposal (e.g. notes, course videos, resources found on the internet) to respond to these questions. However, you are not allowed to communicate with anybody else about this assignment (including, but not limited to: other students currently in this class, prior students, family, friends, or strangers who might respond to online discussion board/forum inquiries). By submitting your responses to this assessment, you certify that you agree with the statement: "I have done my own work and have neither given nor received unauthorized assistance on this work."

I didn't change the length or difficulty of the exams, relative to pre-COVID semesters when these would have been fifty-minute, in-person exams that I proctored. And, as always, I included some high point value higher-Bloom's questions that required paragraph-style writing and, often, opinions (e.g. "State an organism that you think is genetically modified, create your own definition of what it means to be a genetically modified organism, and explain how that organism meets your definition.") I also routinely require students to provide brief written justifications to their answers.

More Cheat-Resistant Questions

I have identified two related strategies for creating exam questions. These strategies can help you easily detect cheating. If you decide to explicitly tell your students in advance about this approach, then it might also help dissuade them from trying to cheat, too!

Strategy 1: create questions that have multiple correct and incorrect answers

The "Genetically modified organism" question above is a good representative of this approach. By asking a student to name one organism (and there are thousands upon thousands of species in the world), it is relatively unlikely that multiple students, by chance (i.e. without working together), will select the same organism. If they do, then that isn't itself proof of cheating, but it might suggest that you more closely scrutinize their written responses to look for other similarities.

Another example of this strategy is, in a genetics class, to ask each student to create the sequence of a mature mRNA molecule that a ribosome would translate into the amino acid sequence: MAYDAY* There are 128 different correct answers to this question. There is a tradeoff between how long the sequence is and how easy it is to score. In practice, picking five or six amino acids creates enough different correct answers and still makes it easy to score. The point is: multiple students submitting the exact same answer, of the 128 correct ones, would be highly unlikely and would be evidence for collaboration (cheating).

In yet another example, I provide students with a pedigree:

and then ask them, "Ignoring the dashed symbols, list all of the possible inheritance patterns." There are six patterns we learn about in class: autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked dominant, X-linked recessive, Y-linked, and cytoplasmic. So, there are lots of possible combinations of those six types, but only one combination is correct. If multiple students submit the same incorrect combination, that could be evidence of cheating.It is important to note, though, that there is always a chance (however small) that two students independently arrived at the same answer. So, it is worth diplomatically approaching accusations of cheating even with this sort of evidence.

Critically, solutions to these questions also are not Google-able: these are unique questions that don't have one correct answer.

I wish I didn't need to employ this approach for virtual/asynchronous exams, but it can be very useful! The idea is simple: if you want to know if your students are posting your exam materials on the web (e.g. on a discussion forum), then efficiency demands that you be able quickly to sift through Google text search results.

When an exam question is written using common words, then there will be many results from a web search…and how many pages of search results are you willing to scroll through? Instead, I now invent scientific names of organisms (like: Albaratius torogonii), or create a unique "sample identifier" (like: "In the pedigree below, with database ID x456gh84i…"). There are currently no Google results for that scientific name and for that identifier, so if I include them in exam questions and students post the question online somewhere indexed by search engines, it is very easy to locate those materials.

This approach has been very successful in helping me find exam questions that were posted to Chegg…and dealing with Chegg will be the subject of an upcoming post!

If you have additional (and ideally no-cost) strategies you have found to be successful at preventing cheating and/or detecting it, please leave a comment below!

Monday, May 31, 2021

Summer Reflections: Academic Dishonesty: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

As I've been dealing with pervasive academic dishonesty (cheating) this past spring semester 2021, I'm now reflecting on what more I can do to prevent cheating. I've written on this in the past, in regard to designing cheat-resistant assessments (and subsequently here), and I will write yet another new post on the same topic in the near future. However, I think some prophylactic measures are also in order. Armed with the knowledge of how academic dishonesty accusations are handled at my university, and having now read the related policies, I'm planning for how to convince students to stick to the straight and narrow.

Although details will different from school to school, definitions of academic dishonesty, and the potential punishments, are often the same. My new strategy is simple: provide direct instruction about academic dishonesty policies and practices at the start of the academic term. Have you, as an instructor, ever done that before? I always assumed that, by the time students were upper-division undergraduates, they would have learned what not to do…but it turns out, I was wrong!

Definitions

My university's Academic Policy Manual defines academic dishonesty in a number of ways, including, "Seeking Unfair Advantage to Oneself" and "Giving Unfair Advantage to Others," and that policy's appendices contain great examples of various forms of cheating. In particular, I was intrigued that academic dishonesty, which includes plagiarism as a broad category of cheating, also involves practices that students are not usually aware will get them into serious trouble, like "Including references in the Bibliography that were not examined by the student."

Punishments

As I read our policy on academic dishonesty, I was expecting to find punishments like earning zero points on the assessment, or failing the course. Indeed, our policy allows the instructor, on their own, to lowering a grade, assigning a zero or F grade for the assignment, or assigning an F for the entire course. However, one other possible punishment really caught my eye as an opportunity to share with students how their carelessness with honesty could ruin their academic lives.

Not only can an instructor also recommend (through our formal process of reporting academic dishonesty to the Dean of Students) that a student be suspended or expelled for cheating, but they can suggest that the student not be allowed to repeat the course for credit. Depending on the course, that could be a really impactful punishment.

For example, the course I'm dealing with now is typically a junior-level biology class that is both required for the major and also a prerequisite for other required classes in the major. So, I certainly plan to make this clearly known to my students in the future: if they're caught committing academic dishonesty, then, after having spent two or three years in the major, they might not be able to continue because they can't earn the degree without passing this class.

Normally, our students take solace in our university policy that a small number of units can be repeated for grade substitution (students who earn a D or worse can repeat a class, and if they earn a better letter grade then it will replace the original grade on their transcript). However, following the discovery of cheating, and then assignment of an F grade for the class, that grade substitution process can also be removed. In my course, a student would have wasted years of time and money and be left with no option for completing the biology major requirements. They might still be able to earn a bachelor's degree, but they would have to change majors, which would incur more time and expense.

I'm hoping that posing such scenarios to students at the start of the term will help deter potential cheaters from following through.

Summary

Please don't assume that your students know all of the various forms of academic dishonesty and all of the potential consequences. In the past, on the first day of instruction, I merely pointed out to students all of the required university policies contained in the syllabus that they are required to read. However, I will be integrating active discussion of academic dishonesty into my classes to make expectations (and especially the potential consequences) more clear!

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Summer Reflections: Academic Dishonesty: Should you trust your students?

I'm a trusting person, until the trust is lost. As an instructor, I see a lot of the opposite, with colleagues that don't trust students until that trust is built. Should I be more skeptical and more wary?

All of the university classes I taught this past semester were virtual and synchronous, because of COVID-19. In one upper-division undergraduate course I taught, which is required for our majors, I tried to design the assessments to be cheat-resistant (which generally worked well, I think). However, it became clear by the end of the semester that some students did commit academic dishonesty, and that is the basis for this thread of posts.

Even though I spent more time than I care to admit dealing with administrative policies and in one-on-one conferences with suspected cheaters, I did learn a lot, and that's the reason I'm sharing lessons learned.

Ultimately, nine of the seventy students in my class provided me (inadvertently) with evidence of academic dishonesty. So, cheating is abundant, although I can't tell whether this is exacerbated by virtual instruction or not. The students definitely argue that it is, based on procrastination, inability to focus, and other factors (comments I'll also leverage later when I write about setting assignment deadlines…).

Will this influence my future teaching? Absolutely, but only in positive ways. As I'll explain in upcoming posts, I'll be even more thoughtful about designing cheat-resistant assessments, and I'll also spend more deliberate time discussing cheating with my classes. Much of what I will say might go right in one ear and out the other, but some of my interactions with cheaters this semester have been real eye-openers about student conception of what is reasonable and what is wrong, what they think constitutes cheating, and the forces that promote cheating.

Despite the unfortunate cheating events in this class over the past semester, am I less trusting now? Absolutely not. There may be the rare bad apples, but I won't let them spoil the bunch. And here's why.

At the beginning of the semester, one of my students posted in the Zoom chat window an invitation to join "GroupMe." Being unfamiliar, I asked what that was about, and a student responded that this is an app that lets anybody create an online forum that people can join and essentially conduct a large, ongoing group chat. In the prior semester (Fall 2020), I had also had a student in one of my classes initiate a GroupMe group for that class, but I hadn't paid any attention. Now that the same app had appeared again, I began to suspect that it is a common practice for students to generate a Group for each class, each semester, to conduct who knows what sort of behind-the-scenes communication, not involving the instructor. I was curious about what might go on in these sorts of open online forums, so I eventually decided to try to join.

The way GroupMe works is that the person that starts the Group provides a registration URL, which requires a name and email address to be provided to request to join the Group. Then the person that started the Group receives those requests and decides whether to admit each person. Although I'm not at all proud of this, I submitted a request under a different name, and not using my professional email address…and I was approved to join the Group. Let the subterfuge commence.

Except…not. The dialogue that ensued usually had to do with class, but not always. Sometimes posts were about current events in the world, or local social opportunities. The most frequent types of posts from students were of two types:

- Did I miss something / what are we doing next class / when is this assignment due / do we have class today?

- Can somebody point me to the chapter/lecture where we talked about topic _X_?

Basically, the most interesting thing I learned from my GroupMe experience is that students apparently prefer to ask each other about class details, instead of asking me (the knowledgable party) directly. Due dates, whether we have class today, whether I've already posted the lecture slides in advance of class…they all seem to be questions that I am best suited to answer, yet the students never asked me.

I must say, in conclusion, that I don't mind this - students often have opportunities (in person) to discuss such topics with each other, and to seek clarification. This is normal, and totally fine. However, it has given me pause about how I can help make these topics even more clear.

Should I try to join GroupMe groups as the real me, so students can ask via chat? Probably not.

Should I create a policy that I'll be active in my learning management system (LMS) website and that I'll respond to posts on our Q&A Forum as quickly as I can? Maybe.

The most important thing I discovered, however, is that nobody ever used GroupMe to cheat. I assumed I would observe rampant cheating using this online tool, but I never did. There are two probable reasons for this:

- Most of the seventy students in the class joined the Group, and because they don't all know each other, they probably feel they can't trust each other. If one student tried to cheat, they risked a goody-two-shoes student alerting me about it. And, I think that would actually happen: I had two students in my class contact me individually to alert me about other types of cheating they had noticed over the semester. Thus, given a large enough class, I would think it likely that any group-based discussion would be relatively safe from cheating.

- There are other, safer ways to cheat. There's no need to cheat publicly using GroupMe when small groups of students that do know each other from prior classes (or for other reasons) can get together offline, or using another app, to cheat. This is the more traditional form of cheating in online/asynchronous classes, I think, and I definitely found evidence of this during the semester as well.

In sum, I've returned to square one. I do trust my students to be academically honest, and I won't be worried about students electing to use methods I don't establish and control to converse with other students. However, I'll still be as wary about cheating, because it does still happen, and perhaps more easily for online classes and especially on asynchronous, untimed and open-resource exams. And that's where I'm heading in the next post, when I'll begin to discuss how I have designed and will redesign classes and assessments to be more cheat-resistant.

Summer Reflections: What's in store

Now that a full year of pandemic (virtual) instruction is behind me, I'm energized to conduct some retrospective analysis: lessons learned and new ideas for moving upward!

Here are some of the themes that I'll cover this summer on the blog, as we begin to prepare for a new year of instruction!

Academic dishonesty in an online world

- Should you trust your students?

- Preventing cheating

- Preparing for cheating

- Detecting cheating

- Handling cheating

- Chegg

- Student interactions

- University processes

Assessment

- Setting assignment deadlines

- Providing timely feedback

and more!

Sunday, January 3, 2021

If you record it, will they watch?

I’ve been a lecture capture advocate for years, but that was before virtual instruction and the purposeful push to build more flexible online classes. While my YouTube analytics from past semesters told me that students do take advantage of recorded content, it certainly isn’t every student that does this. I was curious whether my upper-division genetics class redesign this past fall, in which live attendance via Zoom was not required, influenced the use of lecture capture videos.

Fortunately, Fresno State added Panopto to our portfolio of digital tools just before fall term began. The video analytics reports are great when integrated into our LMS (Canvas), because Panopto logs all video accesses by individual user! So, finally, I have a dataset for some deep investigation.

Ultimately, I find that no simple metric of video use (like number of minutes watched, or view completion) correlates with student performance. However, not surprisingly, student attendance at synchronous class meetings statistically correlates with earning a top quartile total score. Student feedback suggests that the flexibility of recorded class video provides a benefit to those with conflicting obligations. Further, the vast majority of students reported relying heavily on lecture capture video, which should motivate instructors to adopt or continue the practice of providing such videos for their students.

About the focal course

69 students were enrolled in Biology 102, which is an upper-division genetics class that is required for our biology majors.

Attendance

Attendance started strong, with only a few students missing the first day of class. Given the COVID-19 pandemic and all that was going on in mid-August 2020, I was impressed this many successfully navigated Zoom and Canvas and were able to log on. However, attendance quickly plummeted to an average of around 50%, which is much lower than typical for my prior face-to-face semesters for the same course.

|

| Course attendance |

I was pleased to learn that my course redesign helped students in the pandemic era, and that the reduced synchronous attendance was often by choice of students that had other priorities:

“I had work every day during the time that the synchronous classes were live.”

“I had to do school with my younger brothers”

“worked 2 jobs this semester”

“I've had to work much more than usual”“I attended when I could but the lecture being smack in the middle of the day made it hard for me to attend every time with also working 2 jobs.”

Video usage

- The course involved 45 instructional sessions of 50 minutes, which should yield 2,250 minutes of lecture capture, but I had a bit more, because I also recorded my discussions with students after class was dismissed each day (2,364 minutes total).

- 25,902 minutes of lecture capture video were watched

In general, this is a good sign, I think. On average, that’s 375 minutes of video watched per student. But, no student is average, so let’s delve into anonymized individual data.

Student Data

I’ll take this opportunity to point out that many of the following graphs have their x-axes reversed (with small values on the right and large values on the left, near the origin).

Across the semester, I had two students who each watched over 2,500 minutes of video. However, it is important to note that even though Panopto noted that the videos were played for that amount of time, that has nothing to do with whether the students were actually engaged in the material. Regardless, it was discouraging to see that a third of my students viewed fewer than 100 minutes, with seven never taking advantage of those course materials.

With that information in hand, I was then curious how those minutes of viewing by individual students were distributed: did they watch a couple segments of videos over and over again, desperately trying to grasp some concept, or were they sitting down and watching entire videos at a time? Although I don’t yet have the qualitative data to address this detail, I do know that, on average, only two students watched 60+ minutes per individual video. To me, this pattern might suggest students who didn’t attend class and were generally watching each class from start to finish.

I also don’t know (yet) how “minutes watched” was influenced by students watching lecture videos at enhanced speeds (like 2x) or skipping around through the videos. One student did comment,

“Would rather just watch on my own time instead of having to sit there 50 mins, I could watch maybe 30 mins of it on 1.5x speed or skip through parts I didn’t need.”

Critically, the majority of students watched between 5 and 45 minutes on average. This suggests to me that I should further consider how I produce and curate videos: perhaps some short ones for the students that don’t tend to watch lots of video and a time, as well as the full-length lecture capture for students that want that experience.

Then I began to wonder whether and how often each student was making use of the videos. This histogram shows that less than a quarter of students even took a peek at 2/3 or more of the class recordings, with over half of the students viewing any part of 1/3 or fewer of the videos.

Attendance, redux

Returning to attendance, I was curious how a remote, virtual experience influenced individual attendance patterns. The histogram below shows that about a third of my students were regular attenders, present on Zoom between 80 and 100% of our class meetings. Many of the rest attended sporadically. Survey responses from students suggest some of the reasons why, which leveraged the flexible course design I created. I had told students that synchronous attendance would not be mandatory, and that they would be able to review lecture capture videos afterwards when they were not able to (or chose not to) attend. Students were prompted to describe “aspects of the online course design that were beneficial in facilitating the ability to complete the course asynchronously:”

“I did not attend the live sessions and I am doing well on my own. The asynchronous aspect of this course greatly helped me have time to deal with attending school while handling daily life.”

“I worked more Asynchronously towards the end of the semester, and I found that the class recordings were adequate for me to accomplish the homework.”

“The way the class set-up in my opinion was perfect. Many students like myself have had to pick up extra shifts at work just to make ends meet. Having the class set up as non-mandatory attendance allows students to work and attend class at the same time. Students can rewatch the class session they missed at their convenience and still do well in class.”

“The asynchronous aspect helped me out, especially when I had to put focus on other classes, then I could come right back and not be left behind.”

“I felt very comfortable going throughout this course asynchronously. I was able to work more hours and support myself through this.”

In sum, for the population I serve, students who chose to respond indicated most frequently that work schedules, and prioritizing efforts in other courses, were the main causes of non-attendance.

Attendance, video use, and student performance

Finally, let’s explore the interplay between synchronous attendance and asynchronous video use, and grades. Perhaps some of the students who didn’t watch much video were the ones who attended regularly? Maybe the students who watched a lot of video were ones who rarely or never attended synchronous sessions? Hopefully those who attended and/or watched more video earned better grades in class?

In the following scatterplots, the percent of the 45 synchronous sessions attended by each student (each point) is plotted on the y-axis. The students have been divided into approximate score quartiles, where the black squares represent students earning the bottom 25% of scores, the yellow diamonds the next higher quartile, and then the green circles, with the blue triangles being students earning the top 25% of scores.

What I’m looking for when analyzing these plots is whether one or both axes discriminates the four groups of students: do the quartile datapoints (like colors and shapes) cluster together? If they do, then the variable on the axis that creates such clusters is correlated with student performance.

Comparing attendance to total minutes of lecture capture video watched, I see that more video watched (right side) does not correlate with frequency of synchronous attendance (top). Some students watched lots of minutes, attended every class, and were in the top quartile of grades (e.g. upper right blue triangle).

I should reiterate the caveat that lots of video watched (or class attendance, for that matter) doesn’t necessarily mean the student was really getting anything useful from the experiences.

More upper quartile students attended regularly and watched no video (upper left blue triangles). Some high-performing students only attended around half of the synchronous meetings and still earned upper quartile grades. Likewise, one student who attended almost every synchronous class earned a bottom quartile score (upper left black square).

Overall, the blue triangles tend to be in the upper half of the plot, indicating that students who performed well were generally ones who attended class at least half of the time. Likewise, the black squares are mostly in the lower half. Using one-tailed unpaired T-tests with a Bonferroni-corrected alpha (significance threshold) of 0.017, I find that the top quartile of students significantly attends more frequently than the next quartile, and the rest of the quartile groups do not significantly differ based on attendance. Thus, in my class, attendance at the optional synchronous course meetings is predictive of student performance.

The unsurprising take-away for instructors and students is that, at least the way I designed my class, encouraging synchronous student attendance is important. Why?

This is a question that deserves more attention in future. I see at least two potential answers that are not mutually exclusive:

It could be that I’ve designed an engaging and informative synchronous experience that helps students learn the course material

However, it might be that the students who were able and/or willing to attend synchronous classes are those who are already strong students or have some other advantage (e.g. not a first-gen college student, or not working in a job during the semester, or not an URM…).

In other words, attendance, as a quantitative descriptor of students, is possibly acting as a proxy for some underlying factor.

View Completion

Perhaps students who watch most of every video they start are the ones who do not attend class regularly. This was my intention with building an attendance-optional class: that students who didn’t want (or weren’t able) to attend a synchronous online class would still be able to access all of the content.

Here I introduce a new metric: average percent view completion.

In Panopto, every time a student begins to play a video, that access records the number of minutes played, and then calculates what percent of the total video length was watched. So, if I have a 50 minute lecture capture video, and a student plays ten minutes, then that is a 20% view completion. If they watch a second class video and watch 25 of 50 minutes, that’s a 50% view completion. What I’ve done here is not necessarily robust: I calculated the average view completion of all video accesses. In my example here, that would be (20% + 50%)/2 = 35% average view completion.

A major problem with using average as the metric is that it is not sensitive to the number of videos accessed, so if a student watched all of one video, and that was it, they’d register as having a 100% average view completion. However, a student who watched half of every lecture capture video would show a 50% average view completion.

Also, it is worth noting that 100% view completion should not necessarily be the goal. One student commented

“I was able to watch during work occasionally.”

If students are only able to watch in brief increments, then I’d rather have that than nothing at all!

When comparing class attendance (y-axis) to average percent view completion (x-axis) below, the quartiles are not distinguished by the x-axis. Ideally, I expected to see that student data fell along a diagonal between upper-left (high attendance; low video use) and lower-right (low attendance; high video use). However, there are high-performing students who didn’t watch much video at all (blue triangles toward the left) and some students in the bottom quartile of grades who look like they watched most of each video they watched.

This plot is deceptive, though, because the two black squares at about 80% view completion only watched two videos, and those were videos from the start of the semester. Their engagement with course materials plummeted after that.

How to Proceed

What useful insights can be gleaned from these data? First, total “minutes viewed” was a huge number at 25,902 minutes. Even if that doesn’t ensure student eyes were watching the video (or listening to it) for each of those minutes, that’s still enough to motivate me to continue providing lecture caption video for students to review.

Because synchronous attendance has a clear (but never perfect) correlation with student score, I’ll continue encouraging attendance as much as possible. Students realize the importance of attendance, commenting:

“Always attend class because it helps students to understand the content better than viewing the recorded video themselves.”

and

“I attended almost every single live lecture, but it was good to know that it’s not the end of the world if I had to miss a meeting since it is asynchronous.”

(THIS! is exactly the goal)

However, I still won’t make attendance mandatory for online courses - at least not in the current circumstance, where students aren’t opting into a virtual experience; it is being forced on them by COVID-19 distancing restrictions.

Also, I am not surprised to find that student completion of videos is low, and that could be for reasons mentioned above (e.g. jumping around inside each video, searching for specific content). I have two related solutions to this possibility that support students:

- Provide additional videos with more targeted content, so that students can watch short and content-specific micro-lectures on specific topics instead of looking through lecture capture videos to find that content

- Likewise, I am providing Tables of Contents to each video, so students can select the appropriate link that will jump them to the timepoint in the video when a topic is starting to be discussed.

In conclusion, and unsurprisingly, some students heavily leverage lecture capture videos, and others do not. There is more of a correlation between synchronous attendance and earning a top 25% score than the effect of lecture capture video watching. Because of the minimal effort required to record and post lecture capture videos, I will certainly continue this practice, with some additional video curation.

As a final note, some students commented on the importance of providing lecture capture videos promptly, and I strongly suggest doing the same. I routinely posted the video within two hours of the end of class, and I received affirming comments like,

“He would record and post his lectures in a timely matter every class period”

so provide lecture capture materials immediately, or at least at a consistent schedule, so that students will come to know what to expect from you. But, the earlier, the better: the goal is to offer students flexibility, and the longer the instructor takes to provide lecture capture video, the less flexibility students have to access it.

Final Thoughts